Preserving the Past Amid Modern Growth

By Berit Mason

with research contributed by Kaylin Ledford

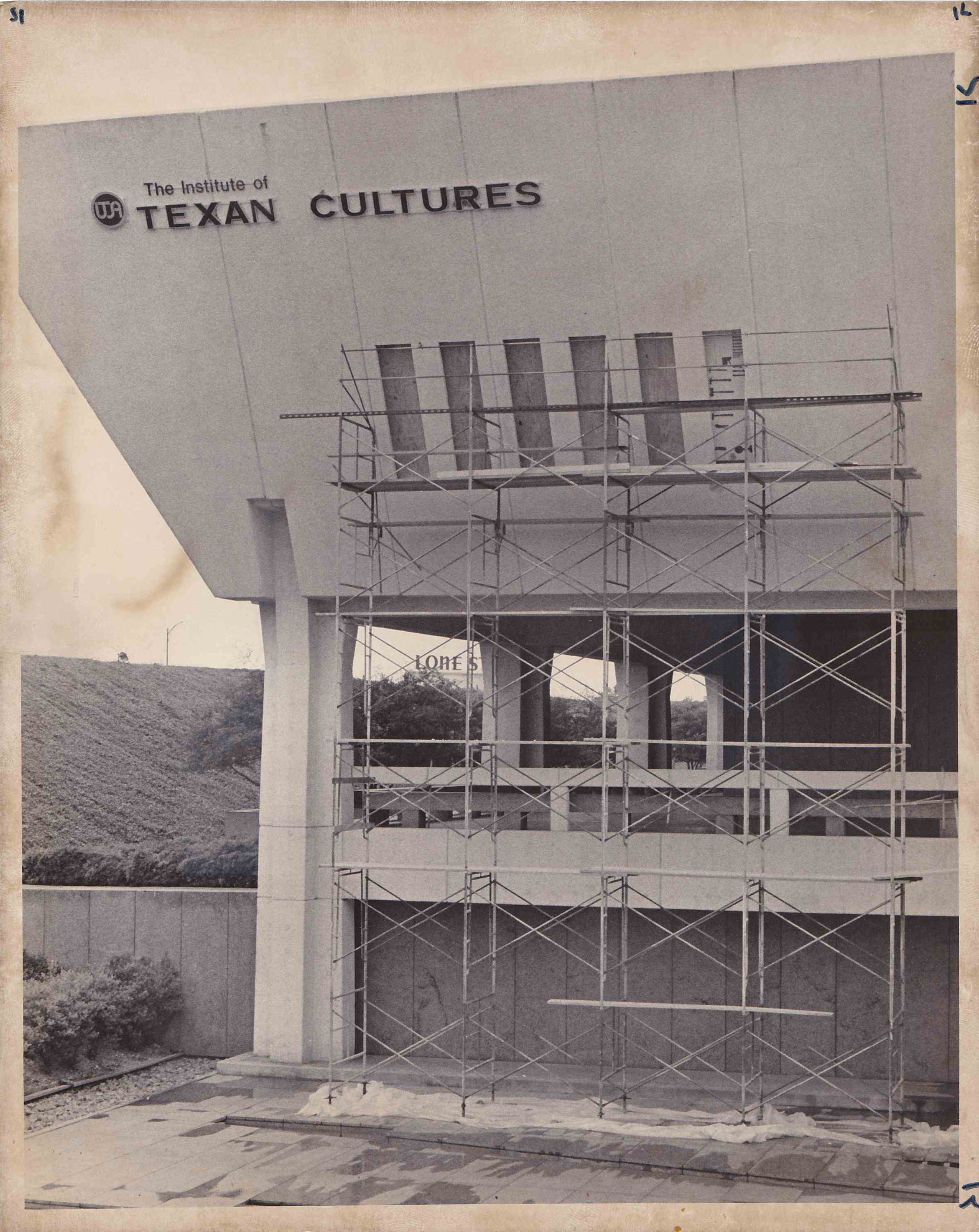

Photo courtesy Institute of Texan Cultures

In what critics call a troubling new precedent, the Texas Pavilion, former home of the Institute of Texan Cultures (ITC), was approved for demolition by both the Texas Historical Commission (THC) and the City of San Antonio, despite the structure’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places and its official designation as a State Antiquities Landmark.

The action, which preservationists cite in new concerns, is part of Project Marvel, a downtown revitalization effort that UTSA and the City say will transform the area around the Tower of the Americas. Critics of the project argue this change will come at the expense of the city’s architectural and cultural heritage.

“It is infuriating,” says Lewis Vetter, president of the Conservation Society of San Antonio, who filed a lawsuit in an attempt to prevent the demolition. He says the Society’s suit was defeated by the powerful legal argument of sovereign immunity.

“Under that, no matter how good your argument is or how meritorious your claim is, it will not be heard if the state chooses not to be sued,” Vetter explains. In a meeting this past April, the THC voted to grant UTSA a demolition permit for the ITC building, which was designed by architect Caudill Rowlett Scott. The permit request was made as the building’s future was still in litigation.

“Federal law has requirements that before a project can get federal funds, a federal agency must do an environmental review and determine if there will be an adverse effect on historic property,” says attorney Catherine E. Courtney, with the firm of Denton Navarro Rocha Bernal & Zech. According to Courtney, there has been no such federal review to date, and she contends that approval of the demolition may ultimately prove to be unlawful.

San Antonio historian Stephen Fox, a Fellow of the Anchorage Foundation of Texas, says the ITC is unique as a Brutalist building and a state pavilion from the 1968 Hemisfair. He says its concrete material and its placement at the east end of the Hemisfair site was intended to reflect a sense of gravitas and institutional dignity.

“It was meant to be a major public building, and to lose that is a tragedy,” says Fox. “It was meant to be monumental.” He believes that more public input is needed before any redevelopment takes place.

To date, it is unclear whether this will occur, although UTSA and the City say they intend to include the public in the project’s future development.

Architectural preservationists say that the city and UTSA are being disingenuous in their redevelopment campaign, using buzzwords like “revitalization” and “sustainability” while sidestepping legal and ethical obligations to historical stewardship.

While the ITC crumbles under modern development pressures, the San Antonio Missions, now part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site and protected by the National Park Service, stand resilient thanks to decades of foresight, advocacy, and archaeological leadership.

In the early 1980s, Anne A. Fox, a respected archaeologist and a direct descendant of Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, conducted pivotal excavations at Mission Concepción and its surrounding grounds. A pioneering force in San Antonio’s cultural preservation, Fox uncovered buried histories beneath the city and championed practices that safeguarded its heritage for future generations.

Her work under the National Park Service and the Texas Antiquities Code preserved the architectural blueprint of the Missions, including the excavation of irrigation canals, buried roadways, and colonial structures beneath Main Plaza and Alamo Street. Fox also laid the foundation for the Missions’ 2015 inclusion as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and went on to receive the title of 1992 Archaeologist of the Year by the Texas Historical Commission. Even amid recent debates over federal defunding of the National Park Service, the Missions remain protected thanks in large part to the groundwork Fox helped establish. Her approach emphasized careful mitigation to protect historical layers beneath modern development—an ethos that could help guide current projects like Project Marvel. This designation, combined with federal and state protections, shields the Missions from the same fate as the ITC. Fox’s legacy proves that proactive preservation—not reactive litigation—offers the strongest defense against cultural erasure. Her discoveries revealed multiple American historical layers predating 1845 beneath downtown San Antonio—structures that would have been lost without archaeological foresight.

Historians say that cultural memory is not just about nostalgia; it’s about identity, continuity, and understanding who we are as a people. When we tear down the physical embodiments of our shared past, we risk severing the ties that connect generations.

As the bulldozers line up to take down the ITC, many are left wondering: If a landmark with both state and federal protections can be demolished so easily, what does that mean for the rest of our city’s heritage? The San Antonio Missions survived because their protectors got there first. The ITC may not be so lucky. ■

The ITC, mid-demolition on May 17, 2025